Program Length: 6 Lessons

Age Group: 10-12 (Grades 5–6)

Author: Alyssa D. McElwain, Ph.D. and Vanessa Harrison, Ph.D.

Preparing for Healthy Relationships:

Relationship Skills for 5th and 6th Graders

Relationships matter, and developing skills to form healthy connections during the years leading up to adolescence benefits young people. Developed for 10- to 12-year-olds, Emerging Relationships is a research-based curriculum that aligns with national standards for school-based health education for use in both school and community settings. Grounded in the six principles of Positive Youth Development (character, caring, confidence, connection, competence, and contribution), Emerging Relationships equips ‘tweens with skills to form healthy relationships with themselves and their peers.

Journals and other participant materials for Emerging Relationships have been translated into Spanish to help better meet the needs of the young people you serve.

*Note: Training is not required but encouraged to facilitate Emerging Relationships. Both in-person and live virtual trainings are available. Call 800-695-7975 or email relationshipskills@dibbleinstitute.org for more information.

Overview

The program’s six lessons teach youth personal responsibility, emotional competence, healthy development, healthy relationships, avoiding risk-taking, and how to share with others what they have learned.

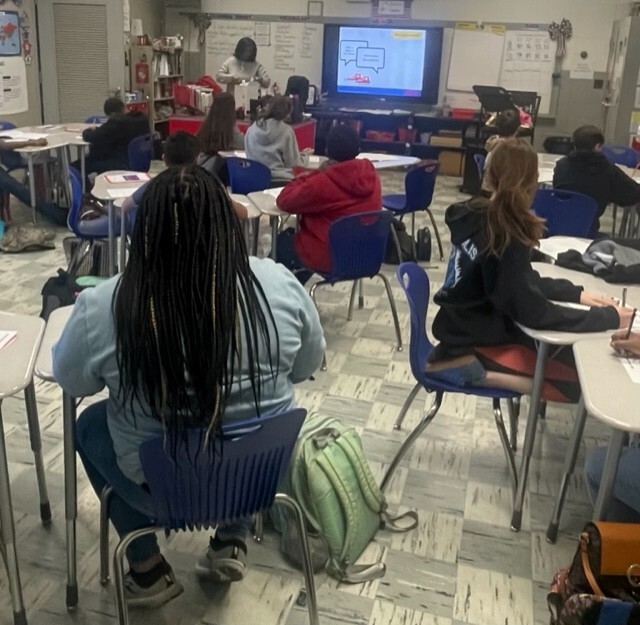

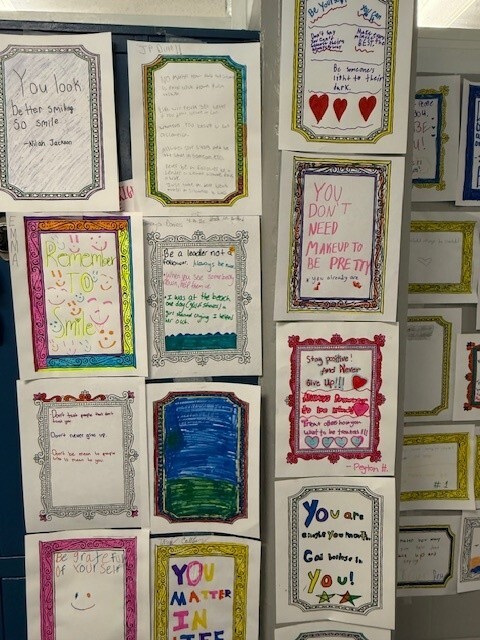

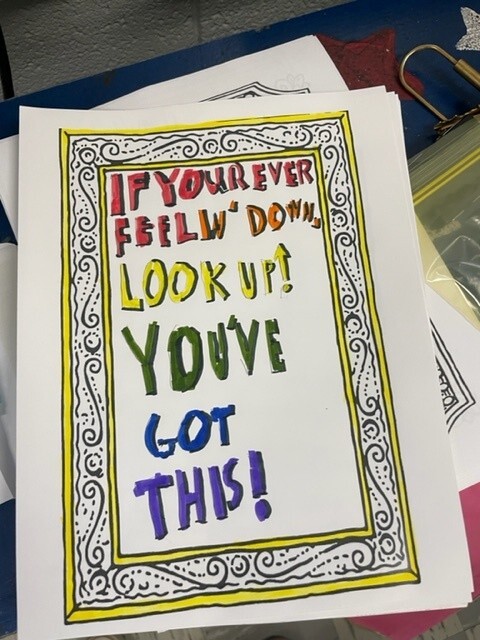

Engaging Content and Teaching Tools

Designed to appeal to youth growing through their “tween years,” Emerging Relationship’s lessons are developmentally appropriate for an audience of 5th and 6th graders. Each interactive lesson gives participants opportunities to practice the concepts while having fun. Participating youth use a student journal, with each lesson offering prompts that allow participants to reflect on and apply what they learn.

Key Topics Include

- Self-regulation skills to enhance mental well-being

- Goal setting

- Healthy decision-making

- Emotional self-awareness and expression

- How empathy, social skills, and self-awareness can impact relationships

- Self-worth and personal strengths

- Prosocial cognitive skills and behaviors to have positive peer relationships

- How to navigate risky situations with confidence

- How to make safe decisions and saying “no” in various scenarios

- Ways to express opinions, preferences, and values

- How to be an advocate for well-being among peers

Learning Outcomes

- Have Character: practice self-regulation skills & healthy decision-making.

- Be Caring: develop personal competence for positive relationships.

- Feel Confident: build knowledge of development & recognize personal strengths.

- Be Connected: recognize healthy relationship traits and practice social skills.

- Feel Competent: develop boundary-setting skills & efficacy in risk situations.

- Make a Contribution: apply knowledge & skills about relationships to help others.

- Program Overview ……………………………………….iii

- Program Objectives ………………………………………iii

- The Science Supporting the Lessons ………………iv

- Tips for Teachers …………………………………………..v

- About the Authors ………………………………………..ix

- Acknowledgements ………………..…………………….ix

- LESSON 1: I AM INTENTIONAL ………………..1

- Welcome & Program Introduction

- I am Intentional

- What Should Remi Do?

- Classroom Commitment

- Wrap Up

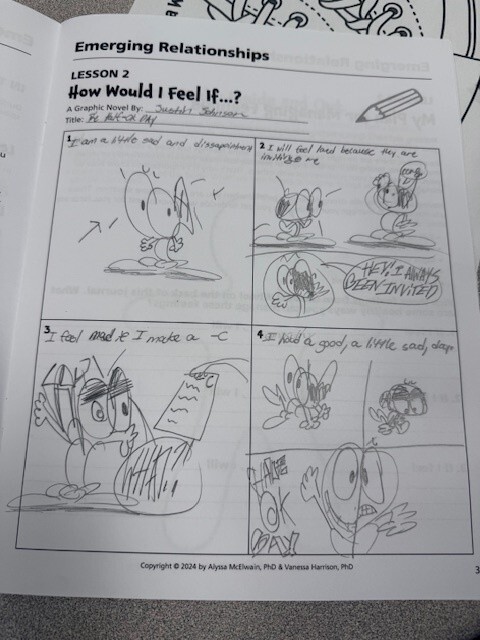

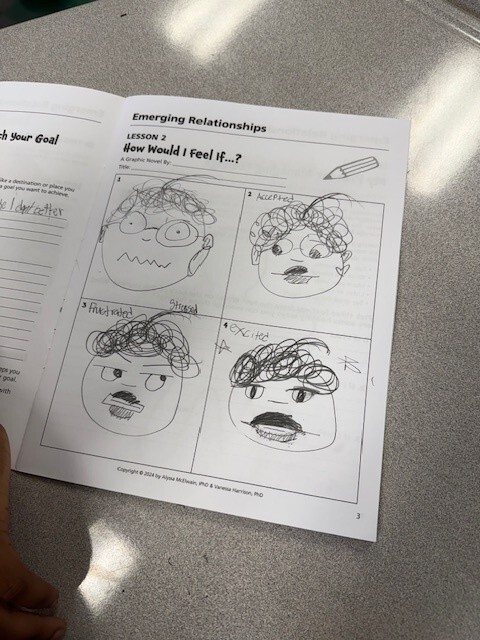

- LESSON 2: I AM CARING ………………………….15

- Welcome & Review

- Overview of Emotions

- Understanding Your Emotions

- How Would I Feel If?

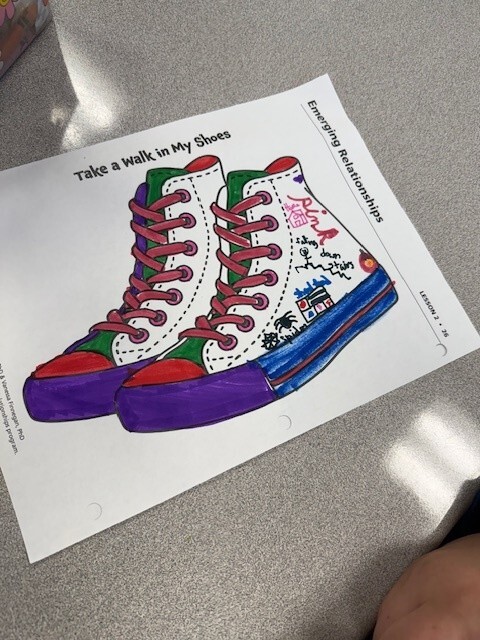

- Understanding Others’ Emotions Through Empathy

- Wrap Up

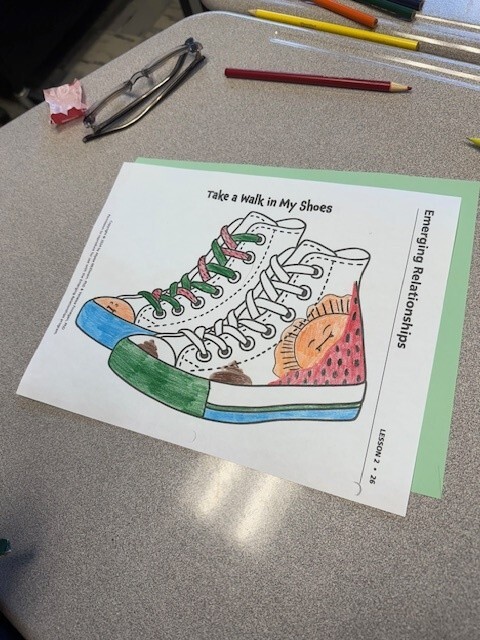

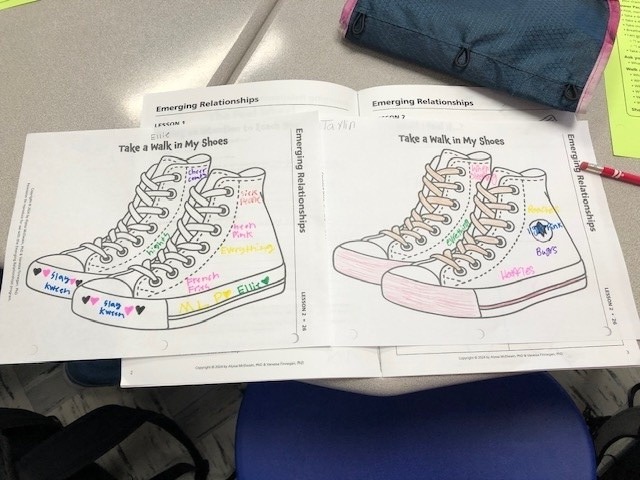

- LESSON 3: I AM AWESOME …………………….27

- Welcome & Review

- I am Awesome

- Brain Power

- Body Beliefs

- Social Skills

- Wrap Up

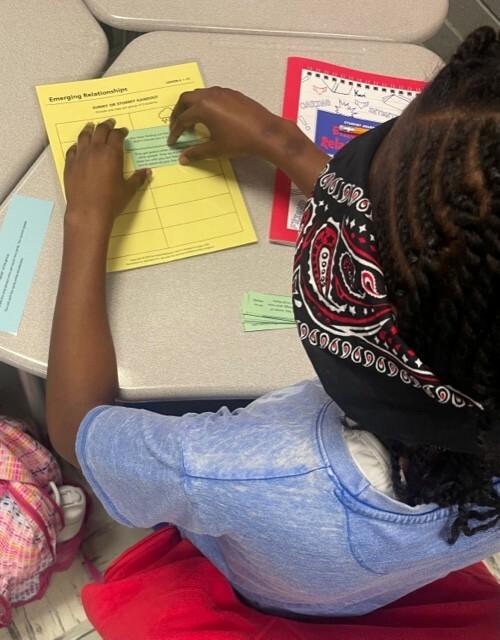

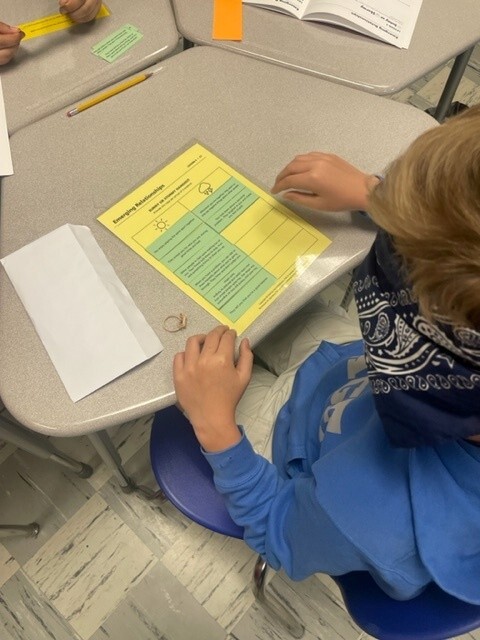

- LESSON 4: I AM A FRIEND ……………………….37

- Welcome & Review

- Sunny Relationships

- Stormy Relationships

- “Sunny or Stormy?” Group Activity

- Wrap Up

- LESSON 5: I AM HEALTHY ……………………….53

- Welcome & Review

- Risky Behaviors

- What are Boundaries?

- My Inner Bodyguard

- Boundary Setting Activity

- Accepting Boundaries

- Wrap up

- LESSON 6: I AM A LEADER ……………………….67

- Welcome & Review

- What is Leadership?

- Giving Back

- Wrap Up

- REFERENCES

Baumgartner, S., Frei, A., Paulsell, D., Herman-Stahl, M., Dunn, R., and Yamamoto, C. (2019).SARHM: Self-regulation training approaches and resources to improve staff capacity for implementing healthy marriage programs for youth. OPRE Report #2020-122. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/sarhm_final_report_september_2020_508.pdf

Bowman, R. F. (2013). Learning leadership skills in middle school. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 86(2), 59-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2012.744291

Brackett, M. A., Bailey, C. S., Hoffmann, J. D., & Simmons, D. N. (2019). RULER: A theory-driven, systemic approach to social, emotional, and academic learning. Educational Psychologist, https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1614447

Brennan, M. (2008). Conceptualizing resiliency: An interactional perspective for community and youth development. Child Care in Practice, 14(1), 55-64 https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270701733732

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Positive parenting tips for healthy teen development. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/pdfs/young-teen-12-14-w-npa.pdf

Collie, R. J. (2022). Instructional support, perceived social-emotional competence, andstudents’ behavioral and emotional well-being outcomes. Educational Psychology, 42(1),4-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1994127

Crone, E. A., & Achterberg, M. (2022). Prosocial development in adolescence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 220-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.020

Damon, W. (2004). What is positive youth development? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 13-24. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002716203260092

Daniels, E. (2011). Creating motivating learning environments: Teachers matter: Teachers can influence students’ motivation to achieve in school. Middle School Journal, 43(2), 32-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2011.11461799

Denham, S. A. (2019). Emotional competence during childhood and adolescence. In V.LoBue, K. Pérez-Edgar & K. A. Buss (Eds.), Handbook of Emotional Development (pp. 493-541). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17332-6_20

Divecha, D., & Brackett, M. (2019). Rethinking school-based bullying prevention through the lens of social and emotional learning: A bioecological perspective. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 2(2), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00019-5

Feng, J. Y., Hsieh, Y. P., Hwa, H. L., Huang, C. Y., Wei, H. S., & Shen, A. C. T. (2019). Childhood poly-victimization and children’s health: A nationally representative study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 91, 88-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.02.013

Ferreira, M., Martinsone, B., & Talic, S. (2020). Promoting sustainable social emotional learning at school through relationship-centered learning environment, teaching methods and formative assessment. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 22(1), 21-36. https://doi.org/10.2478/jtes-2020-0003

Forbes, E. E., & Dahl, R. E. (2010). Pubertal development and behavior: Hormonal activation of social and motivational tendencies. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 66-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.007

Frei, A., Herman-Stahl, M., & Baugatner, S. (2021). Building Staff Co-Regulation to Support Healthy Relationships in Youth: A Guide for Practitioners, OPRE Report #2021-10. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Griffin, L. K., Adams, N., & Little, T. D. (2017). Self determination theory, identity development, and adolescence. Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1042-6_14

Kalb, K. L., McCauley, H. L., Decker, M. R., Gupta, J., Raj, A., & Silverman, J. G. (2011). School bullying perpetration and other childhood risk factors as predictors of adult intimate partner violence perpetration. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 165(10), 890-894. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.91

Lerner, R. M., Alberts, A. E., Jelicic, H., & Smith, L. M. (2006). Young people are resources to be developed: Promoting positive youth development through adult-youth relations and community assets. Mobilizing Adults for Positive Youth Development: Strategies for Closing the Gap Between Beliefs and Behaviors, 19-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-29340-X_2.

Linder, J. R., & Collins, W. A. (2005). Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.252

Malala’s Story (2022). https://malala.org/malalas-story

Maloney, D. M., Ryan, A., & Ryan, D. (2021). Developing self-regulation skills in second level students engaged in threshold learning: Results of a pilot study in Ireland. Contemporary School Psychology (Springer Science & Business Media B.V.), 25(1), 109-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00254-z

Mikami, A.Y., Boucher, M. A., & Humphreys, K. (2005). Prevention of peer rejection through a classroom-level intervention in middle school. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26(1), 5-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-004-0988-7

Moran, M., Midgett, A., Doumas, D. M., Porchia, S., & Moody, S. (2019). A mixed method evaluation of a culturally adapted, brief, bullying bystander intervention for middle school students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 5(3), 221-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2019.1669372

Napolitano, C. M., Bowers, E. P., Gestsdóttir, S., & Chase, P. A. (2011). The development of intentional self-regulation in adolescence: Describing, explaining, and optimizing its link to positive youth development. Advances in child development and behavior, 41, 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386492-5.00002-6

Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Livingston, J. A., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Measurement of the bystander intervention model for bullying and sexual harassment. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 391-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.003

Osmane, S., & Brennan, M. (2018). Predictors of leadership skills of Pennsylvanian youth. Community Development, 49(3), 341-357. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2018.1462219

Pasricha, N. (2010). The book of awesome: Snow days, bakery air, finding money in your pocket, and other simple, brilliant things. Penguin.

Rapee, R. M., Oar, E. L., Johnco, C. J., Forbes, M. K., Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., & Richardson, C. E. (2019). Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, 103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501

Rudolph, J. I., Walsh, K., Shanley, D. C., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2022). Child sexual abuse prevention: parental discussion, protective practices and attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23-24), NP22375-NP22400. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211072258

Rudolph, J. ( 1,2 ), Zimmer-Gembeck, M., Shanley, D.C. ( 1,2 ), & Hawkins, R. ( 3 ). (2018). Child sexual abuse prevention opportunities: Parenting, programs, and the reduction of risk. Child Maltreatment, 23(1), 96-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517729479

Sanders, M. G. (2018). Crossing boundaries: A qualitative exploration of relational leadership in three full-service community schools. Teachers College Record, 120(4), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F016146811812000403

Savina, E. (2021). Self-regulation in preschool and early elementary classrooms: Why it is important and how to promote it. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(3), 493-501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01094-w

Schacter, H. L., Lessard, L. M., & Juvonen, J. (2019). Peer rejection as a precursor of romantic dysfunction in adolescence: Can friendships protect? Journal of Adolescence, 77, 70-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.10.004

Sesma, A., Mannes, M., & Scales, P. C. (2005). Positive adaptation, resilience, and the developmental asset framework. Handbook of Resilience in Children, 281-296. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_25

Shaw, T., Campbell, M. A., Eastham, J., Runions, K. C., Salmivalli, C., & Cross, D. (2019). Telling an adult at school about bullying: Subsequent victimization and internalizing problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2594-2605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01507-4

Smith, A. R., Chein, J., & Steinberg, L. (2013). Impact of socio-emotional context, brain development, and pubertal maturation on adolescent risk-taking. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 323-332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.03.006

Spear, L. P. (2013). Adolescent neurodevelopment. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 52(2 Suppl 2), S7–S13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.006

Thörnborg, U., & Mattsson, M. (2010). Rating body awareness in persons suffering from eating disorders – A cross-sectional study. Advances in Physiotherapy, 12(1), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.3109/14038190903220362

Trach, J., Lee, M., & Hymel, S. (2018). A social-ecological approach to addressing emotional and behavioral problems in schools: Focusing on group processes and social dynamics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 26(1), 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426617742346

Tsang, S. K., Hui, E. K., & Law, B. (2012). Positive identity as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/529691

Vijayakumar, N., Pfeifer, J. H., Flournoy, J. C., Hernandez, L. M., & Dapretto, M. (2019). Affective reactivity during adolescence: Associations with age, puberty and testosterone. Cortex, 117, 336-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2019.04.024

Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Developmental Review, 34(4), 327-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.09.001

Weimer, A. A., Warnell, K. R., Ettekal, I., Cartwright, K. B., Guajardo, N. R., & Liew, J. (2021). Correlates and antecedents of theory of mind development during middle childhood and adolescence: An integrated model. Developmental Review, 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2020.100945

Wolak, J., Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., & Ybarra, M. L. (2008). Online “predators” and their victims: Myths, realities, and implications for prevention and treatment. The American Psychologist, 63(2). https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.111

The Emerging Relationships program is rooted in the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework. This framework is a strengths-based, optimistic view of adolescent development that serves as a foundation for effective youth prevention programs (e.g., 4-H, Teen Outreach Program). Programs using this empowering approach foster adolescents’ potential as key contributors to our society now and in their future.

The learning objectives in the curriculum are associated with helping youth thrive. Specifically, after participating in this program, students will be able to:

- Have Character: Practice self-regulation skills through intentional goal-setting and decision-making.

- Be Caring: Demonstrate emotional competencies such as emotional regulation and empathy that promote healthy relationships and avoid risk-taking.

- Feel Confident: Enhance feelings of self-worth in various domains of development.

- Be Connected: Identify healthy/unhealthy traits in relationships and develop adult— youth mentorship.

- Feel Competent: Develop boundary-setting skills for improved efficacy in avoiding common youth risk-taking behaviors.

- Make a Contribution: Apply knowledge and skills about healthy relationships to advocate for personal and relational well-being among peers.

The Science Supporting The Lessons

Early Adolescent Development

Early adolescence occurs between ages 10–12 when youth transition from childhood to adolescence. Many important changes occur during this period. As youth begin exploring their sense of self, the desire for independence rises. Their ability to control their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors begins to improve, especially with practice. Peer relationships increase in their importance and influence. Youth experience accelerated development changes in their bodies, including sexual maturation and brain development. With so many changes occurring, this stage of life can be both stressful and exciting!

Each lesson in the curriculum is supported by current developmental science. For example:

- Self-regulation—the ability to control one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors—is linked with many positive outcomes in adolescence and adulthood. This curriculum built self-regulation into each lesson by encouraging teacher/facilitator modeling of self-regulation, a “Power Pause” activity to practice emotional regulation, and a focus on goal setting and intentionality. Research shows that self-regulation is a skill that can be improved with practice. Early adolescence is a prime window of opportunity to learn these skills.

- During early adolescence, youth experience significant brain development—specifically, pruning and synaptogenesis. To empower youth, we share knowledge in lesson 3 about their brain development and how they can practice strategies that help them have more helpful thoughts and behaviors.

- In each lesson, students have an opportunity to later connect with a person they look up to or their “Champion.” This Champion Connection is based on research showing that having a trusted adult in their lives makes a big difference for adolescent resiliency.

What do youth need in this stage of development?

According to self-determination theory, individuals have three important psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. When these needs are met, young people have greater motivation, productivity, and well-being. By teaching youth competent decision-making, tools for building positive relationships, and individual character building, we aim to strengthen their overall wellness. This program helps them develop confidence and self-efficacy in navigating relationships and develop a sense of autonomy in their decisions and leadership abilities.

Teachers are crucial in promoting skill development in this curriculum!

The Emerging Relationships program relies on a positive classroom climate and teacher-student connections. As the instructor of this program, your interactions with students will model healthy relationship skills and self-regulation.

Good self-regulation involves having control of one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. A benefit of self-regulation is the ability to focus on long-term goals, manage stress and strong emotions, and behave in ways aligned with our intentions. Adults who interact with youth (parents, teachers, coaches, etc.) have an opportunity to model self-regulation and support youth in developing these skills. This is referred to as co-regulation and has recently become an important aspect of healthy relationship education programs for youth.

Alyssa McElwain, Ph.D., CFLE, is an Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Wyoming. She teaches upper-division undergraduate courses and supervises student internships. Her passion for relationship education programming blossomed while earning a PhD at Auburn University, where she worked closely with her esteemed co- author Dr. Finnegan. Since then, Dr. McElwain has planned, implemented, and evaluated several school- and community-based relationship skills programs for youth and adults. Throughout her career, she has published and presented research on adolescent development, relationships, and evaluations of youth relationship education programs. Creating this curriculum combines Dr. McElwain’s passion for effective pedagogy and the promotion of thriving among young people, both individually and in their relationships.

Alyssa McElwain, Ph.D., CFLE, is an Associate Professor of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Wyoming. She teaches upper-division undergraduate courses and supervises student internships. Her passion for relationship education programming blossomed while earning a PhD at Auburn University, where she worked closely with her esteemed co- author Dr. Finnegan. Since then, Dr. McElwain has planned, implemented, and evaluated several school- and community-based relationship skills programs for youth and adults. Throughout her career, she has published and presented research on adolescent development, relationships, and evaluations of youth relationship education programs. Creating this curriculum combines Dr. McElwain’s passion for effective pedagogy and the promotion of thriving among young people, both individually and in their relationships.

Vanessa Harrison, Ph.D., CFLE, is the Director of Assessment & Strategic Planning for Student Affairs at Auburn University. She leads the planning, implementation, and assessment of strategic initiatives. Additionally, Dr. Harrison is an adjunct faculty member, teaching graduate- level educational research methods and assessment courses in the Department of Educational Foundations, Leadership, and Technology at Auburn University. With extensive experience in planning, management, and evaluation, she has worked on large-scale, federally-funded research projects focused on healthy relationship education. She has facilitated various relationship education curricula for youth and adults in school and community settings. Moreover, Dr. Harrison has trained community educators and university students in best practices and facilitation skills, ensuring effective program delivery aligned with funded research objectives. Driven by her passion for education, Dr. Harrison collaborated with her long-time colleague (and friend!) to develop this curriculum. This endeavor reflects her dedication to a holistic educational approach and the belief that fostering healthy relationships is vital for individual and community health and well-being.

STUDENT FEEDBACK

What did students like about the program?

- “I liked how all the lessons had fun activities.” Female, age 12

- “I liked that the lessons taught us that whatever we say or do can really affect people.” Female, age 12

- “The wheel of feelings and to share.” Male, age 11

- “I liked how we got to learn how to respect others and yourself.” Female, age 12

- “It was inspiring.” Female, age 11

- “They helped me become a better human.” Male, age 12

What did your teacher do well?

- “She shared personal stories and admitted to the wrong things she did.” Male, age 11.

- “She listened to what we had to say.” Male, age 11

- “She told me she would be my ‘champion’.” Female, age 12

- “They taught me well with teaching me life lessons.” Female, age 11

- “She told stories that went with the lessons.” Female, age 12

The most important thing I learned was…

“how to be a better person. Being a better person can get you new, better friends. I learned how to take care of my body physically and mentally. I also learned how to treat others.”

“to not let others treat me badly. Doing this has caused me to be a happy and more confident person.”

“how to be a Leader.”

“that it helped me focus on important things. It helped me learn hot to control my anger and my anxiety.”

“setting my personal boundaries. I can finally say ‘no’ now.”

“to be myself. I learned to be my own person.”

“you have to be a good friend to keep friends.”

“how to set a goal. This matters to me because I want to achieve things in life.”

“to not judge someone. Just be nice to people and don’t never judge someone cause you don’t know how they feel.”

“to set boundaries. And to respect other people’s boundaries. “

“being a good friend. I was able to get closer with my classmates and be friends with them.”

“how to say no and … to control myself.

“to be kind to others because you never know what’s going on with them.”

“that I am amazing and I can tell myself that and others. When I tell myself good things about me it restores self-confidence.”

“how to build relationships. Being truthful to gain peoples trust and be yourself.”

“to treat others with respect.”

“make good choices, you don’t have to act like other people to fit in.”

“relationships. Having a good relationship with your family or friends is always a good thing.”

“being kind. Being kind can chance someone’s day.”

“to always show sympathy or empathy. “

“the important of having healthy friends. A healthy friendship can help relieve stress, help one’s mood, and help meet new friends.”

“be confident in yourself and trust your gut.”

“how to deal with my emotions. I learned you don’t always need to have a bad attitude.”

“to be a kind person and don’t judge others.”

“to stay away from bad things.”

“always be loyal and build a better relationship with your friends.”

“how to be a leader”

“to treat others with respect.”

“be kind to everybody.”

“to always take care of your body and take care of your health.”

“what a a good relationship looks like.”

“Have confidence in myself.”

“all the ways that you can control your emotions.”